The opening shot of Unfrosted shows a young boy packing his running-away kit with favorite supplies, including a GI Joe doll, bubblegum, and a Woody Woodpecker comic. If these early ’60s items inform your personal nostalgia as much as they do director Jerry Seinfeld’s, you are the target audience for Unfrosted, a Netflix film very loosely drawn from the efforts of competing cereal giants to create a pastry-based breakfast tart that could be warmed up by kids in a toaster.

Having hit the road, the little boy finds himself in a diner (another Seinfeldian obsession) where he encounters the comedian, who tells him the story of How the Pop-Tart Came to Be, establishing right from the start that this is a tall tale for children, not a factual account of product development.

This is not the first time the birth of a not-particularly-wholesome foodstuff has been the subject of a studio movie—2016’s The Founder covered the Big Mac, and last year’s Flamin’ Hot was devoted to the Hot Cheeto. But these both purported to depict real people and real events, while Unfrosted, the credits inform us, is “inspired by Jerry Seinfeld’s stand-up comedy.” According to Time magazine, Seinfeld and co-writer Spike Feresten had been airing the idea of making a movie based on Pop-Tarts since 2013 (finally writing a script during COVID lockdown), and Seinfeld has included jokes about breakfast pastry in his stand-up routine for years.

It’s pointless to assess the veracity or otherwise of a comedy routine that may incorporate an actual person or thing, but only as a jumping-off point for ever-more-surreal elaboration and fantasias (e.g., “What if cereal mascots went on strike for more money, and the picket line turned into a demonstration, and the demonstration turned into a Jan. 6–style riot and occupation of the corporate headquarters?”). And Unfrosted is essentially a comedy riff writ large. Nevertheless, there are several elements of truth in it, and moreover, the truth is sometimes even stranger than fiction.

Was There a Cereal War in Battle Creek?

The premise of the film is that the long-term rivalry between cereal giants Kellogg’s and Post came to a head with the race to be the first to develop a toastable breakfast pastry, leading to industrial espionage and no-holds-barred dirty tricks.

There is some truth in this. Kellogg’s and Post did have a long-standing rivalry along the lines of Ford versus General Motors. By the 1960s they did not, as the film suggests, have headquarters across the street from each other in Battle Creek, Michigan, from which they could peer into each other’s windows using binoculars, but both companies had been founded there and were based in Battle Creek until Post moved to Manhattan in 1923 and later to Tarrytown, New York.

Post founder C.W. Post kicked off the hostilities at the turn of the 20th century by stealing a Kellogg’s recipe for corn flakes and rechristening them “Post Toasties.” Oddly enough, considering their later reputation for pushing sugar-laden breakfasts to America’s children, both Post and Kellogg’s grew out of a wellness movement. Will Keith Kellogg and his brother, John Harvey Kellogg, both Seventh-day Adventists, had started the Battle Creek Sanitarium (itself the inspiration for the novel and film adaptation The Road to Wellville), a combination medical center and upscale residential spa that grew out of the church’s small “health reform institute.”

J.H. Kellogg, a confirmed vegetarian, devoted himself to promoting integral medicine and something he called “biologic living,” rooted in the Seventh-day Adventists’ principles of dietary and sexual abstinence. His admirers and patients grew to include several U.S. presidents as well as Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, Amelia Earhart, Sojourner Truth, pioneering investigative journalist Ida Tarbell, and one C.W. Post, who was so taken with the crunchy processed corn flakes and granola-like cereals the Kelloggs served at the sanitarium that he started a company in 1895 that sold remarkably similar products.

In 1906, an infuriated W.K. Kellogg established the Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company, and by 1909 it was selling more than 100,000 boxes of corn flakes a day, leading Battle Creek to be known as the Cereal City.

Post, meanwhile, was equally wellness-obsessed, believing that positive thinking and healthy eating were key. Convinced that coffee was unhealthy, he created Postum, a noncaffeinated drink made from roasted wheat bran and molasses, as well as another plant-based food, 1897’s Grape-Nuts, before launching Post Toasties seven years later. By the turn of the century, the company was turning over almost a million dollars in sales.

Is Jerry Seinfeld’s Character Based on a Real Person?

Seinfeld plays Bob Cabana, a top long-serving Kellogg’s cereal development executive tasked with coming up with a product that will help the company maintain its primacy over Post. Cabana discovers two children dumpster-diving for Post’s trash—not, they explain, because they’re neglected, but because it’s where all the best stuff is, like the “warm goo” in a discarded fruit-filled pastry casing. Cabana realizes Post has figured out how to heat up a tart’s jam-like filling, giving it a huge advantage in the breakfast wars.

In reality, Kellogg’s discovered Post had developed a breakfast pastry not from dumpster explorers or corporate espionage but by the much more prosaic medium of a press release from the company promoting their new product called “Country Squares.” In response, Kellogg’s recruited a food manufacturing specialist from the Keebler biscuit company named Bill Post (you can see why the filmmakers thought using his actual name might confuse viewers). Post helped Kellogg’s figure out how to create a shelf-stable pastry and how to mass-produce it. Instead of bringing in two kids he met in a dumpster for a very small focus group, he brought prototypes home to see what his own children thought of the new snack.

While Post the company was still thinking about how to mass-produce Country Squares, Post the person beat them to it and started marketing Pop-Tarts in 1964. Although the movie suggests the two products came out the same day, Pop-Tarts had a head start and gained first-mover advantage.

Was Marjorie Merriweather Post a Real Person?

In the film, Post is headed up by the forceful, foul-mouthed Marjorie Merriweather Post (Amy Schumer), a bullying boss in jewel-tone sheaths and headwear who is given to throwing things at her put-upon, Smithers-like assistant.

The actual Marjorie Merriweather Post, by contrast, was known for her taste, art collections, public-spiritedness, and philanthropy, supporting institutions including the Red Cross, the Salvation Army, the Boy Scouts of America, the National Symphony Orchestra, and the future Kennedy Center for the Arts. She was also a shrewd businesswoman. After learning from her cook that a company owned by Clarence Birdseye produced excellent frozen fish and meat at a time when frozen foods were generally poor, she visited Birdseye and saw that he had perfected a flash-freeze method that preserved flavor. Initially, her second husband, who was running Post (then called the Postum Cereal Co.), the stockbroker E.F. Hutton, rejected her suggestion that Post acquire Birdseye, but eventually she persuaded him, and Post was transformed into General Foods, becoming a pioneer in the frozen-food industry. The Huttons divorced, but Post remained on the board for 22 years, stepping down in 1958, six years before the Pop-Tart came out.

Did Tony the Tiger Spearhead a Mascot Strike?

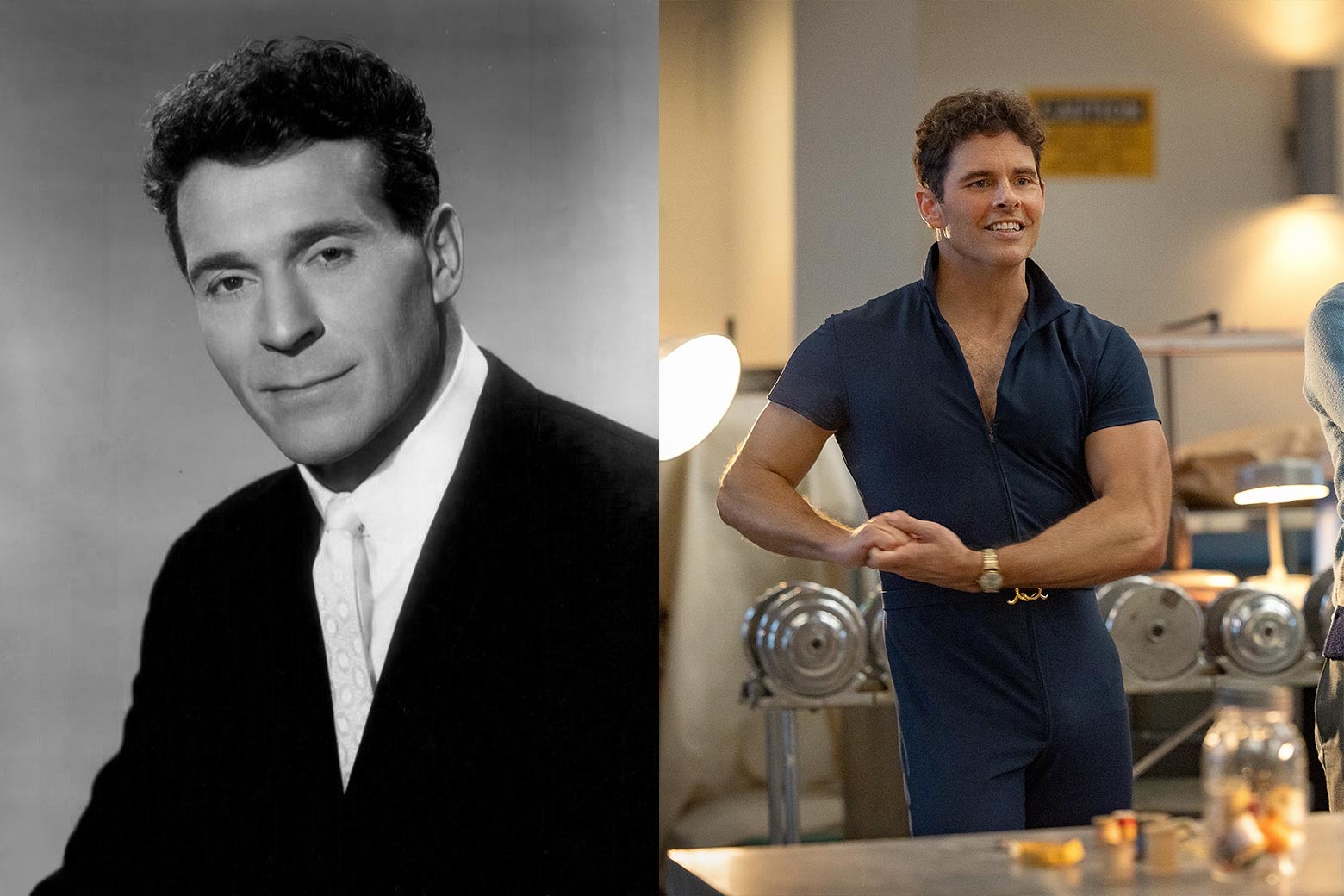

In the film, Thurl Ravenscroft, the actor who voices Frosted Flakes mascot Tony the Tiger with his trademark “They’re Grrr-eat!” (here Hugh Grant, basically playing a seedier version of his Paddington character Phoenix Buchanan), is a hammy British performer who constantly feels his mascot work is beneath him. He becomes dissatisfied with his salary and organizes the mascot actors, eventually storming the company headquarters in bare chest and horned headdress, like the “QAnon Shaman” crossed with a furry.

In fact, Thurl Ravenscroft (his actual name) was a dedicated voice-over actor from Nebraska whose career encompassed being part of the singing group the Mellomen, with whom he sang backup for artists including Bing Crosby, Spike Jones, and Rosemary Clooney, as well as for Warner Bros. Merrie Melodies and Looney Tunes cartoons. Starting with voicing Monstro the Whale in Pinocchio, he spent most of his career doing voice work for Disney productions including One Hundred and One Dalmatians, Mary Poppins, and The Jungle Book, as well as the Pirates of the Caribbean ride. Far from him having an adversarial relationship with Kellogg’s, two weeks after Ravenscroft’s death in May 2005 the company took out a commemorative ad in Advertising Age bearing the headline “Behind every great character is an even greater man.”

Were the “Taste Pilots” Real People?

Desperate for an advantage over Post, Cabana enlists a team of “taste pilots” modeled on teams of astronauts. These include people with a strong personal brand, like TV fitness guru Jack LaLanne (James Marsden), and/or notable grocery-aisle recognition, like Chef Boyardee (Bobby Moynihan). Also enlisted are entrepreneurs identified with products that kids love, like Steve Schwinn (Jack McBrayer), of the bicycle company, and Harold von Braunhut (Thomas Lennon), creator of dubious products like Sea Monkeys and X-Ray Spex marketed to kids in small ads at the back of comic books. With a strong German accent and occasional wistful references to Germany before WWII, von Braunhut seems to be wrestling with an urge to give a Nazi salute as much as Dr. Strangelove or The Producers’ deranged Nazi playwright Franz Liebkind.

The movie suggests Schwinn gave his life for the cause, dying in a tragic accident when an exploding toaster caused a major conflagration during a Pop-Tart test cook. In fact, there was no Steve Schwinn. There was a bike magnate called Ignaz Schwinn, but he had died of a stroke long before Pop-Tarts, in 1948.

Another taste pilot is Chef Boyardee, whose image adorned every label of the canned pasta dishes that brought convenience Italian food to American kitchens. Though he might seem like nothing more than a walking brand image, like Betty Crocker or Uncle Ben, in fact Chef Boyardee was a real person.

Having served as the head chef at New York’s Plaza Hotel, Ettore Boiardi opened his own restaurant in 1924 Cleveland, Ohio, and began selling his spaghetti sauce in milk bottles in response to customer demand. In 1928, he opened a factory and started producing his pasta dishes in cans, marketing it under the name “Chef Boy-Ar-Dee” because it was easier for Americans to pronounce. However, by the ’60s, Boiardi had long ceased to have any direct involvement with the company, having sold it to a conglomerate during WWII when fulfilling an army contract became too much for a family-owned firm.

As for Harold von Braunhut, he was an actual, if improbable, person. His biggest hit, the Sea Monkeys, benefited from an advertising campaign by comic-book artist Joe Orlando that suggested the dried brine-shrimp eggs would grow into a sort of aquatic suburban American family, with Dad in his easy chair, Mom in pearls, and kids playing on the carpet. Disappointingly, the activated Sea Monkeys resembled nothing so much as swimming head lice with short life spans.

However, suggestions of von Braunhut’s Nazi sympathies are not mere dramatic invention.

In 2000, an organization called “The National Anti-Zionist Institute” (for clarity, when it said “anti-Zionist” it actually meant “anti-Jewish”) was found to be concurrently using an address that also processed mail-orders for Sea Monkeys. Another of von Braunhut’s inventions was a pen-sized weapon called the “Kiyoga Agent M5” which could telescope into a metal whip. In 1988 it came out that some of the proceeds from sales of the M5 were going to the leader of the Aryan Nations, and news clippings show that von Braunhut attended the annual Aryan Nations Congress until as late as 1995, sometimes as a speaker.

But the strangest twist in the tale came that same year, when a Washington Post article revealed that von Braunhut had been born Harold Nathan Braunhut in New York and had been bar mitzvahed. He was, in fact, Jewish.